Downsizing Part Two: Automation, Robotics, and the Future of Ageing Societies

When the need to reproduce is severely repressed.

This is part two of a two-part series exploring ageing populations, declining birth rates, and the role of technology in caring for us as we fail to replenish ourselves.

If you missed part one, which looked at the relationship between technological progress and collapsing fertility rates across developed nations, you can find it below.

Land of the Rising Sun

“Eastern ethics, Western technique.” - Sakuma Shōzan, mid-19th-century Japanese thinker.

Japan, 2025. Arguably one of the most advanced societies on earth.

Since the ruins of World War II, Japan has orchestrated a comeback like no other. It’s hard to think of a nation that has rebuilt so thoroughly and hit so many global milestones in the process. The average life expectancy in the island nation rose from around 59 in 1950 to around 85 today; GDP per capita is forecast to reach over USD52,000 by the end of this year; and they have some of the best health outcomes of any nation on earth, offering universal health care and boasting an infant mortality rate of around 2 per 1,000 births.

Japan produces nearly 45% of the world’s industrial robots and ranks among the globe’s top patent hotspots, thanks to its deep public R&D investment.

On the world stage, it also shines bright. Japan is a key member of the G7 and plays an active role in shaping policy on climate, digital governance, and economic security. It has struck major trade agreements, including the EU-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement and the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), positioning itself as both a regional power and a bridge between Western and Eastern markets. Methodically, it has become one of the most globally integrated nations on earth, and Japan’s rise has shown us that being a successful “Western” nation depends less on geography and more on the principles and institutions a country is able to build and sustain.

All of its success has left Japan facing a challenge familiar to many advanced societies: a declining birth rate and an ever-expanding elderly population. Japan’s total fertility rate (TFR) hovered around 2.0 children per woman through the early 1970s, just at replacement level. But it began receiving global attention as fertility fell steeply throughout the 1980s and 1990s, reaching 1.57 in 2000 and bottoming out near 1.26 in 2005-2006. After a minor uptick - back to around 1.42 in 2016 - it’s since descended again, hovering around 1.30 as of 2024.

Even more striking is the pace of ageing. In 1990, people aged 65 and over made up approximately 12% of the population; by 2024, that share has risen to about 29%, among the highest in the developed world.

That leaves Japan in a demographic bind: a shrinking workforce, rising dependency ratios, fewer taxpayers, and a care system increasingly under strain. With no appetite for mass immigration, Japan has instead leaned heavily into automation, robotics, and edlertech.

The Silver Economy

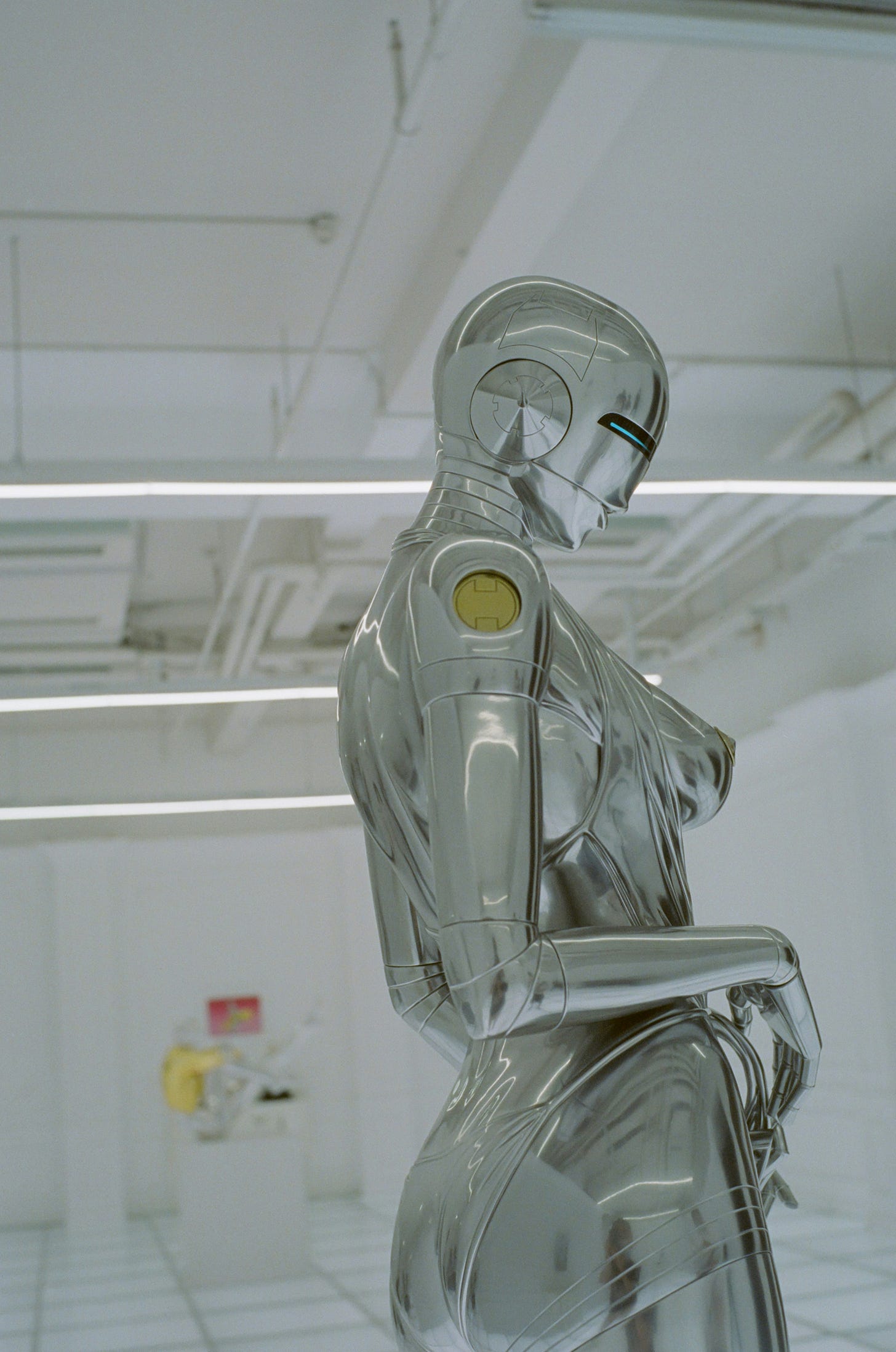

It’s 7:00 a.m. in a nursing home outside Tokyo. Fluorescent lights flicker on, and a soft chime sounds from a control panel. Down the hallway, Robear begins his shift.

Robear is a robot designed to lift patients out of bed, help them into wheelchairs, and transfer them to baths without human strain or injury. Weighing 140 kilos and shaped somewhere between a cartoon bear and a transformer, he’s one of a growing number of assistive robots deployed across Japanese eldercare facilities. He doesn’t talk much, but he’s reliable and gentle, and unlike most staff, he’s not on the verge of burnout. Robear was developed by RIKEN and Sumitomo Riko and has been tested in care settings to supplement human staff.

In many Japanese care homes, scenes like this are becoming the norm. Robots now assist with lifting, walking, conversation, and bathing. Some greet residents at the door, others offer gentle reminders to take medications or drink water. You might, for example, hear Paro - a robotic baby seal used for therapy - let out a soft purr as it responds to touch, calming dementia patients through simple interaction.

Japan’s healthcare system is under immense pressure. With nearly 30% of its population aged 65 or older, and a declining workforce, the country simply doesn't have the human capital to provide traditional care at scale. Nursing shortages are chronic, and younger generations are not entering the profession fast enough. Unlike in many Western countries, there is little political or cultural appetite for large-scale immigration to fill the gap. With no new people coming in, Japan has no other option but to turn to machines.

And Japan isn’t the only one. In South Korea, local governments are deploying companion robots and autonomous assistants at scale. Seoul alone introduced 430 robot-dogs for seniors living alone - robots that can detect emergencies and provide company - and has piloted hygiene robots in care homes to assist staff with intimate tasks like toileting and bathing. RoboCare’s SILBOT and BOMI 2 robots are already operating in over 80 regions, offering cognitive training, medication reminders, fall detection, and even emergency calls - especially for seniors with early-stage dementia.

Singapore, too, is building its silver tech ecosystem. By 2030, one in four Singaporeans will be over 65, and the government isn’t waiting. Humanoid robots like Dexie lead group exercise and bingo sessions in care homes, and early studies suggest loneliness declines when seniors interact with them. Voice-biomarker programmes like SoundKeepers monitor seniors for subtle signs of depression, while AI systems watch for falls and health deviations at home. A*STAR’s programmes are also building more intuitive robots that assist elderly workers and caregivers in public facilities.

While Asia is leading, it certainly isn’t alone. Even in the West, we’re seeing the silver foxes of tech emerge. Carebots are slowly appearing in European eldercare facilities; AI voice systems are being trialed in Canadian and European homes; and governments from Spain to Sweden are investing in edlertech R&D. The plan is clear: if birth rates won’t rebound, and workers aren’t enough, then machines must take on the burden of looking after us.

There’s an APP for that

So, this is where we find ourselves. A society increasingly looking toward cute, anthropomorphised robots to help quell our fear of a lonely old age. Tech has come in like a knight in shining armour and filled the gap our lack of child-rearing has created.

Except, of course, that it’s tech that got us here in the first place.

It was the promise of progress that restructured the family unit. That moved us off the land and into dense cities. That shifted identity away from family and lineage and toward self-realisation, achievement, and productivity. Technology gave us choices, careers, cities, and optional lifestyles, and in doing so disincentivised reproduction.

Now, technology is coming back to ask us to rely on it once again, this time to patch the social and demographic hole it helped dig. Fewer children? Not to worry. Here’s a robot that can lift you out of bed. No one to visit? Here’s an AI system that will talk to you and play chess. Want to stay independent? Here’s a fall-detection algorithm that alerts your care team before you hit the floor. Progress giveth, progress taketh away, progress sells you a subscription to manage the fallout of our declining bodies.

Isn’t it ironic? We optimised life for choice, and now we’re optimising decline for convenience. The same forces that made traditional interdependence feel unnecessary are now designing synthetic stand-ins for it. Only now, care comes in plastic housing, charged nightly and updated over Wi-Fi.

The question isn’t whether this is good or bad. It’s that it completes the loop. The technology that eroded the incentive to reproduce is now being packaged as the thing that will care for us in the absence of reproduction.

We created the conditions to go it alone. Now, the tech is here to make sure we can.

At what cost?

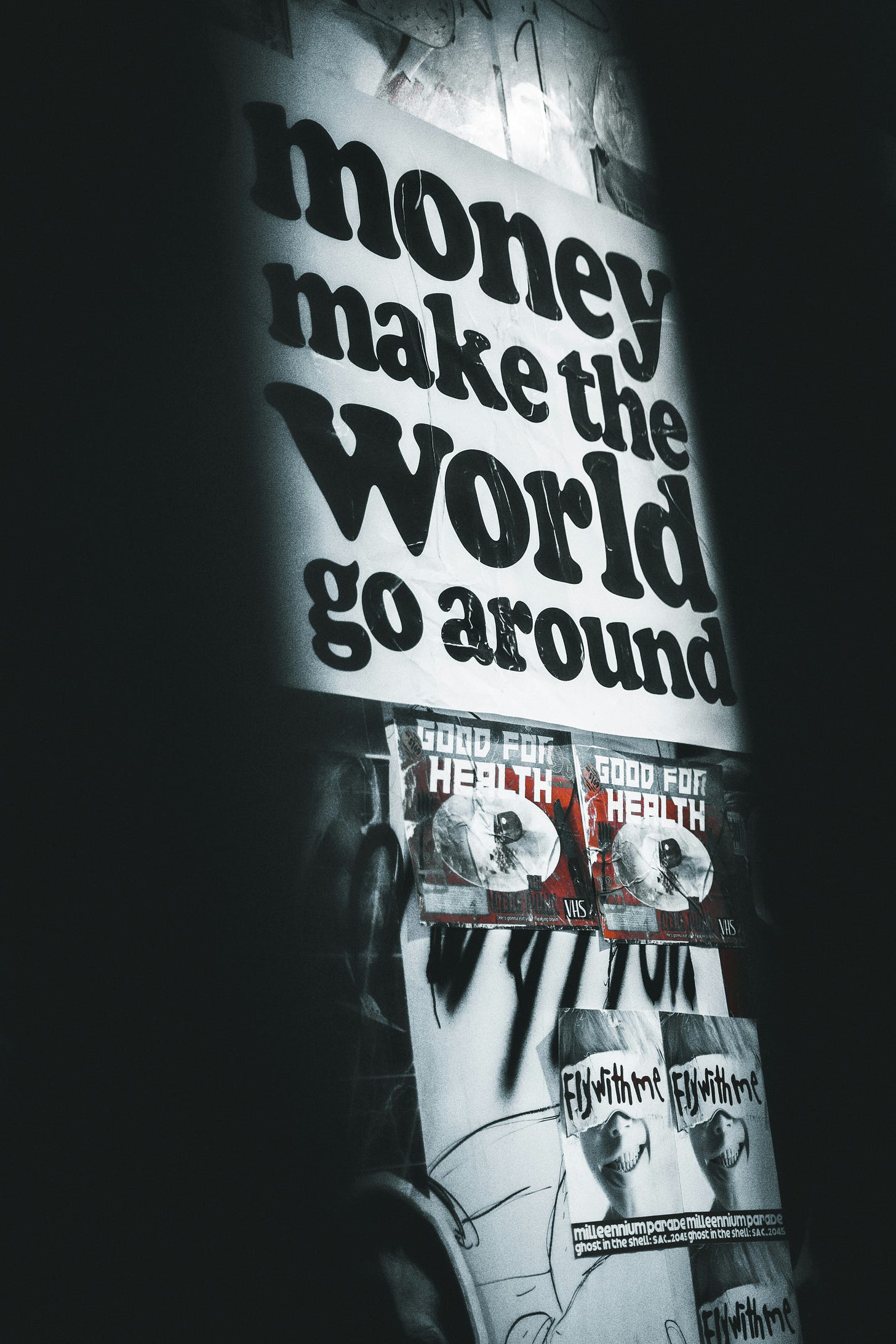

All this innovation requires one very important thing: money.

We often talk about technology as if it were weightless - as if innovation just floated in the ether, unbothered by infrastructure, electricity, payroll, or tax. But progress, especially the kind we’re counting on to care for our ageing societies, comes with a very steep price tag.

As discussed in part one of this essay, having fewer children leads to fewer middle-aged earners paying tax, which means a far higher tax burden on those still in the workforce. That strain was already mounting. Now we’re laying AI on top.

While AI might be helping us in old age, it’s also accelerating the disruption of work in middle age. Agentic AI has been the story of 2025 - autonomous systems performing tasks once reserved for knowledge workers. The white and blue collar backbone of the economy is being hollowed out, not in a mass-layoffs way (not yet, though there have been a few of those in the headlines), but in a slow erosion of roles and responsibilities available to workers.

I wrote about this at length in The Two Worlds Theory (linked below), where I argued that if we get to a point where agents begin to transact economic value on their own - API to API, logic layer to logic layer - then our current tax system will start to look dangerously outdated. If value is going to be created primarily by machines, exchanged by machines and absorbed by the platforms that own those machines, what’s left for the public purse?

One solution I floated was the idea of a logic-layer levy, a digital infrastructure tax that applies not to people, but agents. A system where machine-to-machine interactions are taxed at the point of execution, creating a new pool of public funds drawn from non-human labour. After all, the APIs may be artificial, but the systems they run on are still very much ours.

If we don’t do something like this, we’re left facing a compounding squeeze: fewer taxable humans, with more non-taxable machines. Aside from the budget gaps it creates, it also guts the very mechanisms we rely on to fund care, education, and public health. You can’t build a silver economy on empty coffers.

It’s also become clear that we can’t solve a demographic tax hole with immigration or family incentives alone. In part one, I explored the political backlash already unfolding across the West, from Reform’s surge in the UK to Trump’s immigration-heavy platform in the US. Policy appetite for large-scale demographic correction through migration is thinning. And time is not on our side. If AI is going to help us age with dignity, we need to build economic systems that can keep pace with what’s happening. Not the workforce we wish we had, but the one we’re automating away.

Optimising ourselves out of existence

Once, survival, economic support, and end-of-life care were tied to reproduction. Our existence depended on the social groups we belonged to, the community we built around us, and the children we hoped would outlive us.

Now, those functions are being handed over to systems. Loneliness has a notification, and decline has a sensor. We’ve made life so frictionless, so optimised for independence, that reproduction has started to feel like an inefficiency none of us wants to be burdened with.

At some point, it’s worth asking: if we no longer need others to survive, why would we choose to create more of them?

Throughout these two essays, you may have wondered: if birth rates are declining so dramatically, how is the global population still growing? The answer lies, in large part, in something we haven’t mentioned until now - religion.

While fertility has collapsed in much of the secular, developed world, it remains high in regions where religious belief still plays a central organising role. Countries in sub-Saharan Africa, parts of South Asia, and across the Muslim world continue to see population growth precisely because reproduction is framed not as a choice but a duty. A gift from God. In Niger, for example, the average woman still has over six children. In Afghanistan and Somalia, it’s over 4. Even within Europe, data shows that Muslim populations tend to have higher birth rates than non-religious ones.

I raise this not to draw lines, but to note a pattern: where technology concentrates, religiosity tends to recede. And where religiosity remains strong, reproduction tends to continue.

So, where does that leave us?

One half of the world is giving up on children and increasingly on sex itself. Today’s younger generations are having less sex than any cohort before them, across the US, UK, Japan, and much of Western Europe. The rise of AI-enabled companionship, 4D pornography, and synthetic intimacy is further dulling the impulse to engage, let alone commit. As gratification becomes commoditised, interaction becomes optional.

Where do we split the difference? Will the rest of the world follow the secular, technological path? Or resist it? Will we reach a point where advanced societies are populated by digital caregivers and optimisation loops, while others remain anchored by faith, family, and fertility? Will advanced nations eventually become a version of California? A place where the ultra-wealthy live in algorithmically managed bubbles while everyone else is left to navigate the emotional, economic, and biological fallout?

Could it be that we’re heading toward a bifurcated future - one defined by belief, the other by bandwidth?

Maybe Baby

If you’ve been following my work, you’ll know I tend to write from the intersection of technology, society, and what all of it means for our humanity. But this essay series in particular has brought something new into focus for me.

I’ve realised just how monopolar my thinking has become - how much of what I write about assumes a certain world, with certain values, moving at a certain pace. Western, urban, secular. Tech-saturated. London, mostly, occasionally the US.

But I’m writing this from Bali. And here, the relationship with technology is different. Slower, more hesitant. The divine is still visible, on altars, in routines, in the way people speak about life and death. Yes, I know, it’s my dumb Westerner, “Eat Pray Love,” moment. But it’s also true. There’s more tactile tradition here than there is in London, and I’m starting to think that matters.

The progress of AI and automation isn’t universal. Not culturally or economically, and especially not spiritually. I touched on this far too briefly in A Life Well-Lived in a Post-Work World, where I wrote about the privilege problem: the assumption that everyone will use their time the way a liberal arts grad might. But zoom out further, and the real divide isn’t just how people use their time but who even gets to have that conversation in the first place.

Automation is already exposing the global rift. Some countries are being asked to leapfrog into a post-work world without even having basic infrastructure in place. Others are being handed technologies that might not fit their values, their economics or their concept of what a good life is. If we’re not careful, we’re heading for something worse than inequality: two species of human flourishing. Two models for what life is worth.

What happens when one half of the world is racing ahead - building digital gods, outsourcing care to machines, optimising life into total self-sufficiency - while the other half still believes that creation itself is sacred? That children are a gift, not a cost-benefit analysis? That love, family, and obligation aren’t problems to be solved, but the foundation on which everything is built?

I don’t think humanity is going extinct. But I do think we’re splitting. And we haven’t even begun to grapple with what that means on a global human scale.

Thanks for reading.

If it made you pause, double-take, or even just question the direction of travel we’re on, then it’s done its job.

If you haven’t yet read Part One, I’d recommend starting there.

If you’ve made it through both, I appreciate you.

Feel free to share with anyone thinking about the future in all its strange, uneven glory.

Until next time.