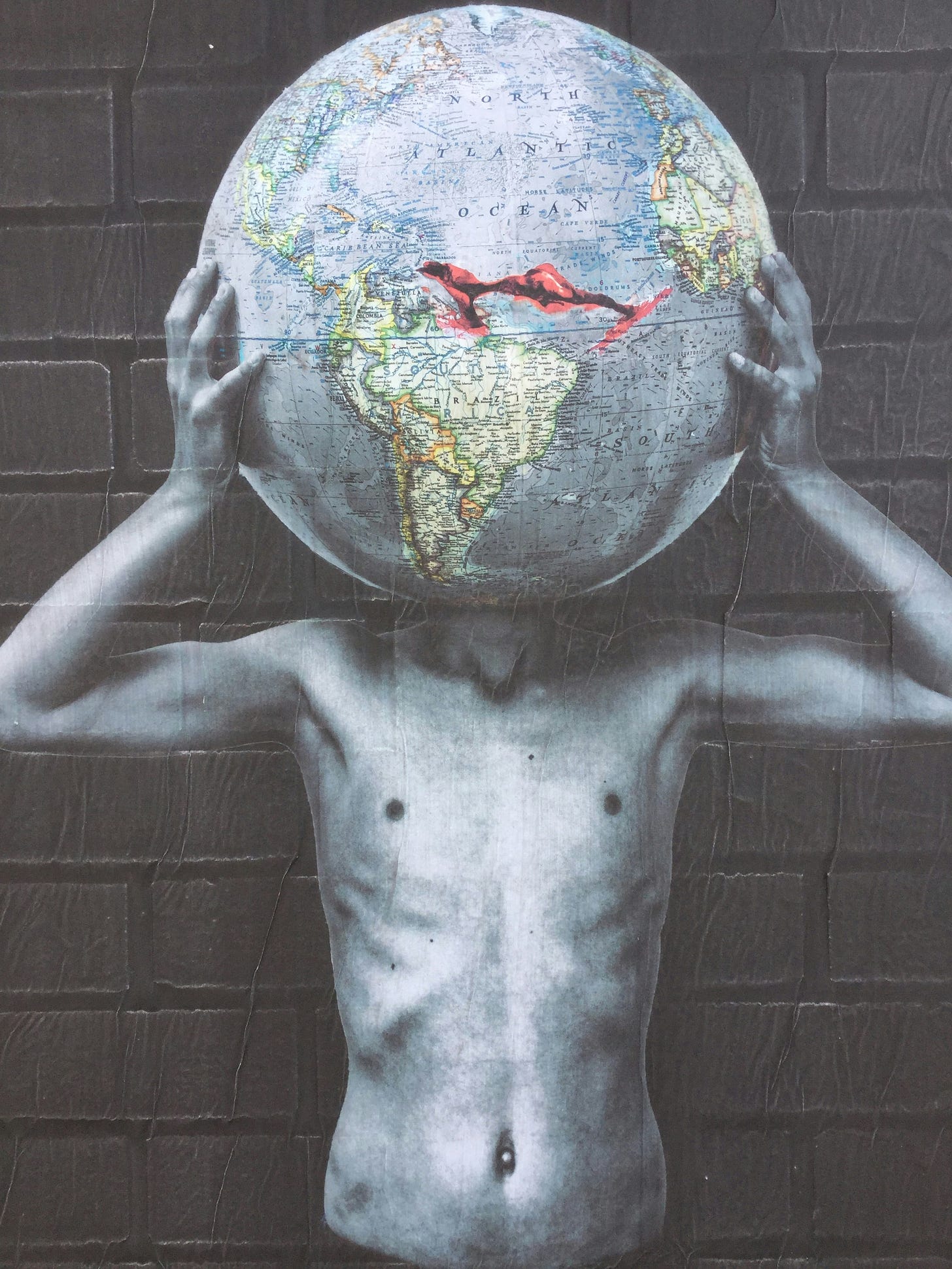

The Imbalance of Progress Part Two: AI's Winners and The Rest of Us

How power, platforms, and politics are shaping who AI works for

This is part two of a multi-part essay exploring the imbalance of progress in the age of AI.

In part one, I looked at how progress spreads and the conditions it depends on. If you haven’t read it yet, I’d recommend starting there. Please see link below.

This essay picks up from that foundation and looks at how the innovation race is unfolding today. Who’s out in front, how they got there and what it means for everyone else. The focus is on power, influence, and the systems being exported as progress.

We already know what happens when a nation wins the innovation race. History, thankfully, has shown us.

The reason we live in a majority Anglosphere world is because Britain won the last one. The Industrial Revolution gave it a lead that reshaped the modern world. With it came a global spread of British systems - language, law, civil service, education. From the United States to India, that influence is still embedded in much of how the world runs today.

Now, AI may be setting the stage for a new version of that same pattern. Swap out steam engines for algorithms and cotton mills for machine-led decision-making, and once again, we find ourselves with one or two nations pulling ahead, setting the rules, and exporting a system in their image to the rest of the world.

The United Kingdom was singularly dominant in the Industrial Revolution: in today’s race, it’s the United States and China.

The American Century

If the Industrial Revolution crowned Britain, the end of World War II handed the sceptre to the United States. The old empire limped out of the war, financially broken and politically spent, while America emerged with its infrastructure intact, its economy booming, and its global influence unquestioned. The US helped win the war and, in doing so, won the right to set the rules for its aftermath. It set up the global institutions that would manage the postwar order: the UN, the IMF, and the World Bank. It installed the dollar as the world’s reserve currency, launched the Marshall Plan to rebuild Europe and ensured that American capital, expertise, and influence became foundational to the West’s recovery.

Of course, it wasn’t just diplomacy or economics that the Americans excelled at; their real lead came in science and technology. Cold War paranoia fuelled a golden age of research. Defence budgets bankrolled the early architecture of modern computing, NASA pushed the boundaries of engineering and DARPA - originally ARPA - seeded the building blocks of what would become the internet. Semiconductors emerged out of military contracts, and universities across the nation became hotbeds for state-sponsored innovation. A system started to form, and infrastructure was put in place to cultivate the genius, the daring, and the entrepreneurs.

Somewhere between academia, the defence sector, and the US government, Silicon Valley was born. By the time the personal computer arrived, the stage had been set, and on it a wave of companies turned wartime infrastructure into the most lucrative commercial opportunity possible. Intel, Hewlett-Packard, Microsoft, Apple.

The 1980s and 1990s paired Wall Street with the Bay Area, and the financialisation of tech created a new kind of engine: one that paired California’s culture of experimentation with New York’s appetite for scale. Venture capital became the growth accelerant, and the startup became a national export. Software began eating the world, and American platforms started building the plumbing of the digital economy. By the time Elon Musk co-founded OpenAI in 2015, the U.S. was the main architect of digital life across the globe. The systems were in place, the platforms were established, and the capital was flowing.

With this came ideology. California was able to export its view to the world. Optimism, openness, scaleups. America was exporting products and assumptions, selling freedom and meritocracy and what the future should look like.

AI was the product of a 70-year relay, from wartime to peacetime, from the military to the markets, from government compounds to mum and dad’s garage. An entire nation prepping itself for a new wave of industrialisation.

China Ascending

Mid-century China looked nothing like a contender. By the end of World War II, it was reeling from Japanese occupation, crippled by civil war, and on the verge of complete collapse. What followed was the rise of Mao Zedong, the founding of the People’s Republic in 1949, and a series of ideological experiments that left deep scars. The Great Leap Forward devastated agriculture and industry. The Cultural Revolution tore through universities and civil society, purging the very talent base a modern economy would need to grow. Where the US was building institutions for innovation, China was unravelling its own. It lost time, it lost talent, and it nearly lost itself to famine and dogma.

This all changed in 1978 when Deng Xiaoping took power and did something few revolutionary leaders do: he pivoted. Under Deng, China began opening up its economy while keeping its politics closed. One-party rule stayed in place, but private enterprise was allowed to flourish. Markets were selectively and strategically embraced under the now famous phrase: “It doesn’t matter whether a cat is black or white, so long as it catches mice.”

While the West saw cheap labour, China was playing the long game.

Through the 80s and 90s, China industrialised at record speed. Infrastructure was built overnight. Special Economic Zones sprang up. The country became the world’s factory and used that status to absorb, adapt, and localise the tech flowing in from abroad. Rather than leapfrogging, it systematically studied the West, mirrored it, and is now trying to outpace it.

By the early 2000s, a new generation of Chinese tech giants started to emerge. Alibaba, Baidu, Tencent. Shielded from foreign competition by government policy and powered by a vast domestic market, they built an entire parallel internet tailored to Chinese consumers, habits, and regulations.

Then came the shift from platforms to intelligence.

In 2017, the Chinese government published its Next Generation AI Development Plan. A blueprint to become the world leader in AI by 2030. The means were coordinated investment, education reform, infrastructure build-out and even closer alignment between the state and private sector. Since then, China has moved with extraordinary focus. Its AI is already integrated across logistics, manufacturing, medicine, and - most controversially - state surveillance. What the country lacks in open debate, it makes up for in execution. While the West debates ethics and data rights, China is busy deploying.

So, that’s roughly where we are. Apologise for the crash course in the history of modern tech, but it matters. Today’s AI race isn’t just about who builds the best model but who sets the rules. The US and China are competing for who gets to architect the future of AI. One is fully focused on commerce, the other is focused on state-led control. The tools might be similar, but the logic behind them isn’t.

History didn’t end. And neither, it turns out, did the Cold War. The US just changed who it was dancing with.

The Rest of Us

We’re the second-tier winners. The UK, Israel, South Korea, and the UAE. Nations that are wealthy, developed, strategically important, but not necessarily setting any rules. These are nations that aren’t building foundational models or exporting their ideology through product design. They aren’t minor players, but nobody is thinking of them as the main characters either.

Some have relevance due to their legacies - former empires, financial hubs. Others are new entrants, small states punching above their weight by betting big on the next wave of innovation. What binds them is that they’re all trying to find room to manoeuvre in a race that’s increasingly being defined elsewhere.

The Aligned Powers

These are the countries that have capability, reputation, and in some cases, global reach, but not full autonomy. The UK has DeepMind, a strong academic heritage, and some of the most active AI ethics debates in the world. But it doesn’t have a home-grown foundation model at scale. Its key player is owned by Google, and its public discourse is often a remix of US talking points. London may have hosted the world’s first global AI Safety Summit, but the infrastructure still lives in San Francisco.

Israel is a powerhouse in cybersecurity and defence AI, largely driven by military R&D and the feedback loop between government, academia and startups. It’s incredibly advanced in narrow applications of AI - targeting, surveillance, pattern recognition - but its influence is more tactical than structural. It doesn’t shape the foundation layer, but more just innovates on top of it.

South Korea is a global leader in hardware and robotics, with strong capabilities in AI-adjacent fields like semiconductors, sensors, and high-performance computing. It has deep tech talent, major conglomerates (Samsung, LG, SK Group), and a government that’s actively investing in national AI capabilities. But again, it’s operating within the architectures defined by others.

The Strategic Modernisers

Then you’ve got nations like the UAE and Singapore. Smaller, more centralised states that are playing a different game entirely. For them, AI is as much about capability as it is about positioning. AI is how they hedge against resource dependency, geopolitical vulnerability, and relevance in a multipolar world. The UAE’s G42 has made some major moves, partnering with Microsoft, launching its own LLM, and building data infrastructure with global ambitions. Singapore is investing in compute, in public-private partnerships, in regulatory frameworks designed to attract international R&D while safeguarding local interests.

All these countries are placing strategic bets on AI. They’re also being pragmatic: they know their models won’t win the race outright, so the play is about leverage. Influence through integration.

The Bystanders

Then there are the nations that don’t have the capital, compute, or control to act independently and are trying to navigate a global order that wasn’t built with them in mind. This includes much of the Global South, but also parts of Europe. These countries aren’t necessarily passive; they’re just severely limited.

Limited in infrastructure. Limited in language coverage. Limited in local datasets. Limited in how much say they’ll get in what these models learn, what they value, and who they benefit.

A new kind of non-alignment is emerging. A blurring of politics and technology. Do you adopt American systems with their commercial dominance and quasi libertarian ethos? Or Chinese systems with their efficiency, integration and centralised control? Or do you try to thread the needle with your own governance layer, without full control of the stack?

The question here moves from tools to values. Whose definition of safety matters? Whose understanding of bias, fairness, transparency, explainability?

On the Edge of Divergence

So where does that leave us?

We’ve got two powers writing the base code of the future. A few others are trying to shape the interface, and most are watching as the new operating system gets installed without their input.

The same tools are being deployed, but not for the same ends. AI is being trained on different datasets, in different languages, by different systems of belief. Regulation, safety, fairness - these are the cultural dimensions that need to be discussed alongside the technical ones.

Everyone is trying to build the world’s smartest system. But whose version of smart gets embedded into the world?

Thanks for reading.

If you’re enjoying these essays and haven’t already, please feel free to subscribe, share them with friends or send me a note.

Next week, in part three, I’ll look at where this is heading. The cultural clash is already emerging between competing visions of safety, bias, ethics, and control.

Until then.

Loved this. Been thinking about the new AI order, and particularly how the UK, with its rich history of innovation (even recently), could better cash in on its contributions in the tech space - rather than selling up to the US.