The Imbalance of Progress Part Three: Those We've Left Behind

A handful of nations are building the future. The rest are trying to survive the present

This is the third and final part of a multi-part essay series on the Imbalance of Progress in the age of AI. Part one explored the conditions that make progress possible, and what’s required for new technologies to take root, scale, and spread. Part two tracked how today’s AI race is unfolding: who’s out in front, how they got there and what it means for everyone else.

You can find both of those linked below.

There are 195 countries on this big blue planet of ours. 195 places that, to greater or lesser degrees, house all the elements that helped our species, Homo sapiens, rise to the top of the food chain. Culture, commerce, government, warfare, language, law. Empire and its collapse. Religion, bureaucracy, digital infrastructure.

All the world’s a stage, and for the last few thousand years, we’ve been its leading stars.

We’re terribly impressive, aren’t we? A networked, global civilisation that is relentless, adaptive, and self-aware.

That is, of course, until you start scratching at it. Start looking at where we often don’t have the courage or the bother. Look there, and you start to notice that roughly half the world lives on less than $7 a day - about what a Londoner or New Yorker might spend on a sandwich from Pret. Look a little closer, and you’ll see the 2 billion people without safe drinking water in their homes, or the billions more who deal with unreliable electricity, intermittent internet, and governments too fragile or corrupt to offer anything resembling what you or I might call “basic services.” Suddenly, our star starts to dull a little.

195 countries, but now let's remove the ones where civil war still rages, where elections are little more than off-West End theatre. Let's also take out places where the only working infrastructure is what foreign investors build for extraction, countries like the Democratic Republic of Congo or South Sudan. With all those gone, that 195 turns into maybe 60 countries that function with any kind of stability.

Scratch that again, and of those 60, how many are economically secure, politically stable, and technologically equipped to shape the next era of innovation?

Not many.

And when it comes to AI - arguably the defining tool of our century - it’s really just two that are setting the pace: The United States and China. Everyone else is choosing sides, playing catch-up, or watching from the sidelines.

That’s the uncomfortable shape of our world right now. Not flat, not equal, not even meaningfully multipolar.

Out of 195 nations, only a handful have a real say in how the future gets written. The rest are just living in their shadow, or better yet, trying to survive it.

The Forgotten World

The world is so big, and we are so small, that it’s completely forgivable that we only ever notice our little slice of it. It’s why we bristle when we’re told we’re not the centre of the universe. Because technically, that isn’t true.

We are.

Not in a cosmic, destiny-driven kind of way, but in the only way that truly matters. Consciousness has no outside view. We don’t observe the world from nowhere; we live in it from one fixed point: ourselves. We are the lens, the interpreter; the universe folded back in on itself, trying to make sense of its own patterns through neural matter and subjective thought.

This doesn’t make our experience universal; it just makes it ours. And it means the parts of the world we can’t see, aren’t wired into, don’t know about - vanish. Not physically, but existentially. What you don’t know is outside the frame.

For most of us in the West, sitting in our South London flats or West Hollywood condos, the AI story is everywhere. Some of us think it’s overdone. Saturated. BORING. For others, it’s very real. They’ve just lost a job to it, shut down a business because of it, or - less dramatically - are just trying to keep up as their workplace gets reshaped around it.

We get TikTok tips on how to ChatGPT our CVs. We complain on LinkedIn about the flood of AI-generated posts. One minute we’re claiming the internet is dead - meaning no humans are left and it’s just bots talking to bots - the next, we’re announcing the end of journalism, advertising, radiography, music videos. Et cetera. Et cetera. Et cetera.

All of this means something to us. To some, it means a great deal. To others, to billions of others, it means absolutely nothing at all.

It’s as irrelevant to them as a rover drilling Martian soil is to us. Or to flip the lens: as distant to us as a Toposa boy stepping on a landmine in Eastern South Sudan - in a war neither he nor you has ever heard of, in a country most people couldn’t place on a map.

(A note to the reader: the Toposa are a semi-nomadic tribe in Eastern South Sudan, largely disconnected from national infrastructure, media, and formal education. Many are unaware of the Civil War, yet are collateral damage.)

That’s what I mean by the forgotten world. The parts of our big blue planet that are still governed by violence, drought, superstition, or pure institutional collapse. Where famine is still seasonal. Where electricity is a rumour. Where slavery, in various forms, still exists.

We tend to treat the Holocaust or the transatlantic slave trade as historically singular horrors. But they weren’t exceptions. They were just the ones that captured our attention. The ones that got remembered. That got academy award-winning films made about them because they happened, or involved parts of the world that aren’t forgotten: Germany and the United States. Places that moved far enough beyond their horrors to name them, reflect on them, and even attempt to atone for them.

That doesn’t make those events any less horrific or significant. It just makes them visible.

Elsewhere, today, countless similar horrors unfold daily — without trials, without reflection, without textbooks or trigger warnings. In the parts of the world that remain outside the frame.

Oh, the Humanity!

There is, tragically, no shortage of horrors I could reference in this essay to land my point. No shortage of misery I could choose from.

I could point to present-day Mauritania, where little Black boys and girls are born into hereditary slavery as if it were 1782 and the abolitionist movement had never happened. Or to present-day Afghanistan, where what we in the West recognise as the patriarchal horrors of the suburban 1950s would be a welcome paradise to the women and girls who are treated worse than cattle. Where they’re banned from schools, forced into marriages before they’ve hit puberty, and risk death for reporting rape.

Places that have never known peace. The kind of peace we in the West have - anomalously - enjoyed for just under a century. A peace so uncharacteristic in human history it almost shouldn’t exist. But it does, and it wholly shapes and distorts our worldview.

I don’t know what moral calculus we use to decide which horrors matter most. Why this year is the year of Israel and Palestine. Yes, October 7th ruptured something. But there were other ruptures, too. In 2024, the Sudanese army and RSF turned Khartoum into a desolate battlefield. Over 14,000 people were slaughtered. Hundreds of thousands displaced. The UN warned of ethnic cleansing in Darfur - again - and barely anyone noticed.

Five years ago, it was the Assyrian. Hunted across Syria and Iraq, their churches bombed, their towns emptied, their language nearly wiped out. A civilisation with roots older than Christ, erased in a decade. Go five years before that, and it was the Yazidis. Rounded up by ISIS, men executed, women trafficked, children indoctrinated. More than 3,000 Yazidi women and girls are still missing today. The UN rightly called it a genocide; it got a long read in Foreign Affairs, but there was no mass protest, no viral hashtag. No urgent call to do much of anything.

And none of it has been resolved. We’ve just stopped looking.

We’ll move on from Israel and Palestine. Just like we did after the Oslo Accords in the 1990s. Just like we did after Arafat died in 2004. Just like we moved on from the Yazidis, the Rohingya, the Assyrians. Just like we’re already beginning to move on from Ukraine and Russia. We move on. But the people living it don’t.

But let’s step away from the edges of the truly grotesque and dwell, just briefly, on the barely livable. Places that aren’t pockets of hell on Earth - just chronically hard to survive. Countries like Chad, Haiti, or the Central African Republic. Not war zones, necessarily. Just states too brittle to build anything lasting. Where there’s no public trust, no decent roads, no stable currency, no coherent infrastructure, and therefore, no plan on how to move forward. People aren’t being bombed or sold, they’re just trying to live without water, wages, or hope.

Their suffering has even less of a chance at making the headlines or getting a trendy hashtag going. But they do represent the daily reality of hundreds of millions of people.

For Whom the Bell Tolls

I’ll admit, writing this essay hasn’t exactly lifted my spirits, and I imagine it hasn’t done anything for yours either.

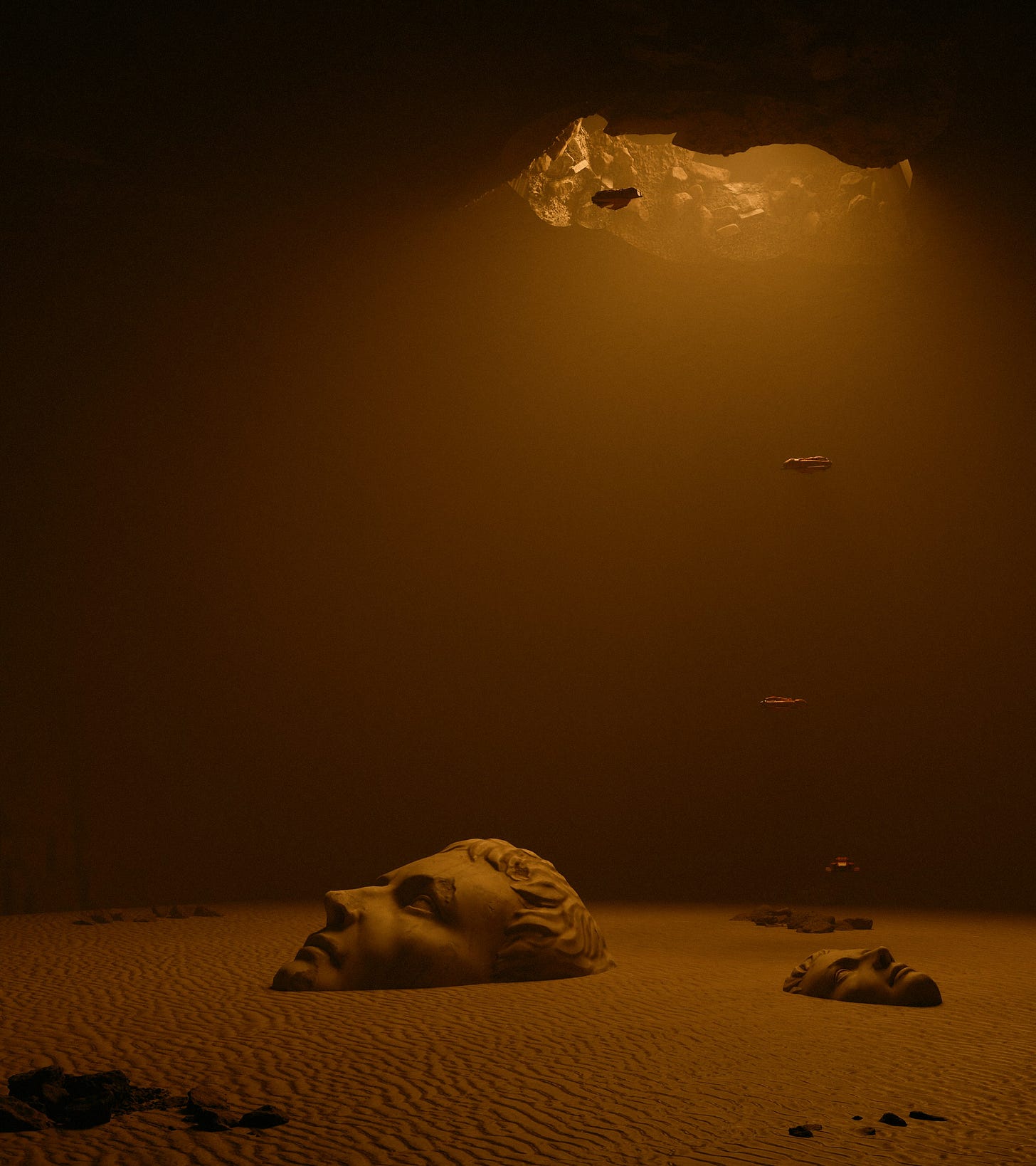

Most of what I’ve laid out so far is bleak, because most of what I’ve found is bleak. And that’s kind of my point. We’re racing into a new technological age without ever getting the old one right. We haven’t solved water, or housing, or basic literacy in half the world. We haven’t reckoned with slavery, genocide, or the collapse of fragile states. At best, we’ve learned to look away faster and protect our little havens that aren’t burdened by these things. We’re off building digital dreamscapes while millions live without a plug socket. Debating AI ethics while actual ethics - human rights, dignity, survival - remain unsettled and out of reach.

And now here comes another rupture: a planetary tool being designed in a few postcodes, sold as if it’s for everyone, and spreading faster than we know how to govern. We’re being told not to worry. That personalised superintelligence will live in our glasses. That universal basic wealth will level the playing field. That every problem you can think of - education, health, creativity, climate - has a model waiting to solve it.

Maybe.

But for whom?

For the teenager in Seoul training LLMs on multimodal datasets? Or the one in Sanaa watching their school get shelled?

For the Bay Area founder with three agents managing their calendar? Or the rice farmer in rural Myanmar who’s never seen a working desktop in his life?

This is the dissonance at the heart of everything we’re building. The story of AI isn’t just about the technology; it’s about the substrate it’s being poured into. And that substrate - culture, infrastructure, governance, belief - is wildly uneven.

In California, there are neighbourhoods that feel like the preludes of a post-scarcity society. Climate-controlled, algorithmically scheduled, drone-delivered paradises. If pockets of hell exist on this planet, so too do pockets of heaven. Matha’s Vineyard. Palo Alto. Aspen in July. Worlds where everything is buffered, optimised, invisible. Where labour is outsourced and inconvenience is a UX flaw, not a lost limb. Where even boredom has been engineered out. It’s from these places that AI’s loudest promises are being made. A vision of the world where you’ll never need to remember, calculate, or plan ever again - your agent will do it all for you. Sam Altman recently floated the idea that AGI would generate so much value, it could fund a new economic model for the entire human race.

Okay, sure, but how does that future arrive? Does the California OS get airdropped into the Sahel? Does Boko Haram get access to autonomous planning tools? Do the sacred and the synthetic get forced into coexistence?

We’ve barely begun to process what that means.

We talk a lot about inclusion. About equity, about belonging. In the West, these are full-time jobs and conference panels backed by corporate mandates. We debate the tone of onboarding emails while entire nations remain un-onboarded from modernity itself. And yet, when it comes to AI, we speak as if its benefits will just…flow. That abundance will trickle outward. Once the models are trained and the system is stable, the rest of the world will somehow catch up. No friction, no fallout. No need to ask what it is they’re even being included in.

But what if that’s not what happens? What if the incentive to include the rest of the world just isn’t strong enough? What if the cost of bringing the whole world online, not just technically, but socially, spiritually, politically, is too high, and slow, and messy?

The truth is: most of the people building this future don’t think about the billions who won’t be part of it. Not because they’re cruel but because they don’t have to. The market rewards optimisation, not uplift. It’s engagement we’re after, not education. Integration, not accommodation. There’s no go-to-market plan for the Toposa. No roadmap for reconciling AGI with Wahhabism, or for installing autonomous agents in countries where electricity is rationed by the hour. And yet we talk as if we’re only a few policy papers and NGO grants away from a “just transition.”

But we all know this train isn’t waiting for anybody. And once systems start running, it’s very hard to retrofit equity into them. Ask any developing country trying to rewrite its data laws after a tech giant has already extracted value from their population.

Which leaves us with the harder, more uncomfortable question: What if we’re not trying to include the rest of the world at all? What if the default plan - not out of malice but just cause it’s too damn hard to solve for - is to build for those who are ready and leave the rest behind?

Leave the World Behind

I started writing about AI for the same reason a lot of you started reading about it - curiosity, anxiety, the sense that something big was happening, and we weren’t quite sure what it meant.

When I published Leave Thinking Behind, I was focused on people like me. Knowledge workers. Nine-to-fivers. The people whose jobs were suddenly being nudged sideways by a GPT. It was a conversation about “us” - and by us, I meant the people who read essays like this for fun. The ones with enough margin in their day to think about what thinking even is.

But over the course of writing this collection of essays, that “us” has started to feel far too narrow. Not because more people are paying attention, but because most of the world isn’t in the picture at all.

AI will continue to accelerate. And in doing so, it will help us accelerate everything else: medicine, science, logistics, energy, and even planetary exploration. The kinds of futures that make for dazzling keynotes and speculative novels. I do not doubt that a better world is possible. A world where suffering is reduced, labour is optional, creativity is abundant, and life extends in both directions. But when that world arrives, it won’t be for everyone.

How do we square a future where some people have robots caring for them into their 90s, while others still die before 10? Where we send probes to the moons of Jupiter, while whole nations still can’t guarantee electricity?

Even if we crack interplanetary travel - even if the physics lines up and the code complies and all systems are go, not everyone will get a seat on the ship.

People will be left behind.

We know this because we’ve already left so many behind.

We already live in a split reality: one part synthetic abundance, the other systemic neglect. One part simulation, the other starvation. The divide isn’t coming; it’s already here.

Progress will continue. But the idea that it's ours, or universal, is the biggest fiction of all.

Thanks for reading.

As ever, if you’ve made it this far. I appreciate it. If this piece resonated, please consider subscribing, sharing, or sending it to someone you think might value it. Always open to thoughts, responses, and disagreements.

Until next time.